Emilia Phillips

Emilia Phillips on Self-Celebration and Writing About Desire

Maria Bowler interviews the poet Emilia Phillips about her work, poetic education, writing about desire, and turning self-deprecation into self-celebration. Emilia Phillips (she/her/hers) is the author of four poetry collections from the University of Akron Press, including the Embouchure (2021). Her poems, essays, and criticism appear widely. She’s an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at UNC Greensboro.

I’m really interested in the deft way you handle the body within your work, particularly the way it simultaneously illuminates desire and alienation, joy and pain. Have there been any particular writers or thinkers that have informed your approach to writing about the body?

Thank you so much for your kind words about how I write about the body, Maria, and thank you for inviting me to be interviewed.

I grew up with a forensic scientist father, which is kind of an odd start to a life thinking about the body. I’ve told this story elsewhere, in my poetry and lyric nonfiction, but I mention it here because I think it might unpack a narrative of growth in the way I’ve handled the body. In my first book Signaletics, I was writing about forensic science and its relationship to the body, but I was perhaps also unconsciously adopting a clinical approach to the body. Throughout my next two collections, Groundspeed and Empty Clip, I was trying to face my own body, the realities of it, sick at first, then mentally ill.

While trying to do that, I really turned to a number of writers. Among them are Lucy Grealy (Autobiography of a Face), Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (The Body Keeps the Score), and poets like Lynda Hull, Etheridge Knight, Adrienne Rich, Aracelis Girmay, Jenny Johnson, Morgan Parker, Dana Levin, Marianne Boruch, Gwendolyn Brooks, Claudia Rankine, and so on.

Continuing on this theme, I’m wondering if you can talk a little about how the theme of desire has informed your writing of the poems in Embouchure, your newest poetry collection coming out next year!

The new book is trying to make self-deprecation, especially the telling of embarrassing or awkward stories, into self-celebration. Some of that embarrassing and awkward stuff is desire: who was I attracted to? Well, turns out, mostly women, even though I spent most of my life in a straight-facing relationship with a cis man. The book is then, perhaps, my coming out book. Someone, maybe Danez Smith, joked on Twitter something like “All poets have coming out books. Some of them just do it later in their lives.”

*tentatively raises my hand*

(Of note here, too, is that after I came out, I went back and looked at my previous books and I count no less than three poems per book that could be read with a lens of queer desire. There are a lot of stockings in my books!)

“I Tried to Write a Poem Called ‘Imposter Syndrome’ and Failed”, which recently appeared in Poem-a-Day, is a great example of how you playfully manage self-revelation. I’m thinking in particular of the line, “ I made myself / laugh and so I made myself hurt— // MEMOIRS BY EMILIA PHILLIPS, goes the joke.” To what extent is the notion of “confessional poetry” useful or alive to you as a writer? What about as a reader?

When I first started learning about poetry, a teacher told me that “confessional poetry” was easy. Unartful. It was especially associated with women, too. You know what, I’ve had to work long and hard on combating my internalized bias against confessional poetry. Sometimes, you need to say what you need to say without (f)arting it up, you know? I once co-led a poetry retreat with Chen Chen and he had this wonderful workshop on The Art of Telling, a kind of directory of loopholes in the “show, don’t tell” mantra we teach our students. I loved that class, and I felt all over again that great wash of a student’s curiosity by sitting in on Chen’s class. What did I need to say and hadn’t yet, couldn’t yet say? Why was I coding everything in metaphor? In the scaffolding of a project? Who does it benefit by me not coming right out and saying something? It was Chen’s writing exercise that conjured a poem in the forthcoming book, “My OB/GYN Suggests I Consider Cosmetic Labiaplasty.” For me, confessional poetry has a great deal of power because it reveals the internal lives of those who have been systemically—historically and presently—oppressed by patriarchal, white supremacy. Yes, I have privileges as a white person, but as a woman there were so many things about which I had shame. I wanted to get over that shame by disempowering it. And how do you disempower shame? By not allowing the things about which you’re ashamed to remain secret. That included sex, gender, sexuality, body size, etcetera. But sometimes I feel “confessional” isn’t quite the right word for what I mean. “Confessional” implies a dark box in which you whisper your secrets to an anonymous priest. “Confession” implies shame.

Maybe we can come up with another phrase that doesn’t carry all that connotative baggage of shame!

How does your process differ (if indeed it does!) for your lyrical nonfiction work and your poetry? Is there any difference in the impulse to write in “prose” versus poetry? Do you know when a piece is “finished” in the same way?

For one thing, I can’t write lyric nonfiction at all times, but I can generally find my way into working on a poem at any time of the year. I have to be on an extended break for me to even begin thinking about lyric nonfiction—an essay’s arc, structure—and it’s usually after a fallow period, a break where I try to reset my brain. That’s why my lyric nonfiction is usually written in the summer. I often find myself in hyperdrive with writing poetry during about a 2–3 week stretch every early fall and every early spring. I’m such a seasonal person! I try to eat seasonally! I listen to music seasonally! Of course I write seasonally too. As far as finishing a piece, I never think the essays are done. Sometimes a poem comes to rest, which is what I like calling it rather than that it’s “done.”)

As a professor in the MFA Writing Program and the Dept. of English at UNC – Greensboro, how has teaching informed your writing life? Has it changed over the course of your teaching career?

I’ll give a specific, extremely recent example here. This semester, I assigned my Grad Poetry Workshop a translation project while also doing a Latin-American Poetry Translation independent study with one of those grad students. Reading and spending time with poetry in another language, or else translated into our own, has been one of the most life-altering, poem-metamorphosing experiences of my life. In that class, I’m learning alongside my students, which allows for more of an exchange—a conversation—between us, which gives me that same rush of energy and excitement that I felt as a student. So, yes, it’s changed for the better. Especially when we embark on projects together.

You’ve written thoughtfully about the role of education and your own formation as a writer. How does the writing advice you give now as a teacher differ (or intersect with) the formation you received as a student?

Oo, boy. I could take you down some roads, particularly with regards to one kind of “old guard” poetry education I received early on, but I saw something different when I went to my MFA program, especially with my thesis advisors David Wojahn and Kathleen Graber. It’s so strange because I invoke them in almost every class, sometimes parroting their advice. It’s just nickel-and-dime stuff, David says, I say. But I find myself increasingly having revelations about something one of them would try to teach me at the time, that I thought I got but I never really did. It’s only now that I realize how much time and energy and thought and heart they put into teaching me. I’ve also realized what an overwhelming student I must have been! (I was always in their offices, asking them to read new poems or recommend me books.) That being said, I do think that my tastes for poetry—indeed, poetic aesthetics—might be a little more expansive than some of my teachers. Things they might have steered me away from I push my students toward. I’m not sure that’s a good thing. Maybe it means I’m a less discerning reader than they are.

You’re an active and generous presence online, particularly on Twitter. What has that community and engagement meant for you?

This is a hard question because I am lately resisting these online spaces, in part because it sometimes lacks nuance, especially when it comes to the behavior of real people and their opinions. I try to avoid scandals and limit my intake of the news. For me, I want to use these spaces only as a place for access, to share poetry, nature, and so forth. I’m glad I’ve arrived at this place. It’s so much healthier, and it allows me to associate the poetry community with community, not confrontation.

Lastly, what’s next for you? And that can include rest! Are there any challenges or projects you’re excited to explore?

Rest? What rest?

I’m kidding, of course. I rest here and there in the midst of projects rather than at their ends. Someone once told me, and probably someone else will correct me, that Lucie Brock-Broido would wait at least 100 (maybe 200?) days after finishing a collection to write again. That’s not me. My collections, how they interact with one another, is a little accordion shaped, where the end of one book is pressed face to face with the beginning of the next. What I mean to say is that I’m working on projects that overlap with one another.

Right now? I’m working on a poetry collection called La Dichosa, which is the title character of a poem by Chilean Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral. The moniker roughly translates as The Lucky/Joyous/Fortunate/Blissful One, gendered feminine. The poem features a speaker who has left behind her family, community, and possessions for a “plain wall and a conversation” with a beloved, who remains cleverly ungendered in the poem. Mistral has romantic relationships with women, albeit she wasn’t—like most queer people at the time—out. I have done a “queer” translation of the poem, which serves as the book’s proem. In the second half of the book, I have a sequence of poems in the voice of this character La Dichosa, more about her living a non-normative (definitely queer and possibly ethically non-monogamous) life. As I write this in the middle of the COVID-19 social distancing order, I’m very interested in being “alone with someone,” how you collaborate on a mythology of the rest of the world through your language, your conversations. That’s what I’m trying to explore there.

The first section of the book is also in persona: Eve, as in “Adam and.” My Eve is sexually and romantically disinterested in Adam, and she tries to create another woman throughout the course of the twelve-poem sequence. Of course, being my Eve, her language is anachronistic, her culture hyper-American but fantastic. The sequence is meant to cast the Garden of Eden as the ur-narrative of compulsive heterosexuality.

Other than that, I’m trying to add more to Wound Revisions, my collection of lyric essays I mistakenly thought I was finished with last summer. (I’m thinking one, maybe two more essays?) That project has been going on for almost eight years now.

Like a clock without hands, I’d be lost without at least one project. (And two helps me better account for the minutes.)

Phil Christman: Examining Culture, Geography, Capital, Class and Future-Making

Maria Bowler interviews Phil Christman on his new book, Midwest Futures.

Phil Christman

In his new book Midwest Futures, Phil Christman examines culture, geography, capital, class, and future-making through the notoriously ill-defined region of the Midwest. A former substitute teacher, shelter worker, and home health aide, he currently lectures in the English department at University of Michigan. His work has appeared in The Hedgehog Review, Commonweal, The Christian Century, The Outline, and other places. He holds an MFA from the University of South Carolina-Columbia. He is the editor of the Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing, a journal sponsored by the University of Michigan's Prison Creative Arts Project. Midwest Futures is released from Belt Publishing on April 7.

Inspired by the way the Midwest was surveyed into six-by-six square mile grids, you organized the book into 36 1000-word “plats” or squares. What was it like writing prose within that constraint? What did it allow you to do, or think about?

I mean, for one thing, it was really useful for letting me know when I was done! This topic is infinite and I kept wanting to read five more books, then five more books, then five more books. It also kept the book short—I always wanted it to be something you could fit in a stocking and read in an afternoon. I was thinking of books like Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? or Kristin Dombek’s The Selfishness of Others—a kind of tightly coiled book, a book that feels like an unexpectedly intense conversation that you can’t pull away from. (I can’t know if that’s what I achieved, but it’s what I was after.)

You begin the book with a historical anecdote that shows how “ungraspable” the topic (and, indeed, the geographical reality) of the Midwest is. What drew you to taking on such a notoriously fuzzy subject matter?

It’s kinda funny—everything I write that anybody likes ends up being about the sorts of large, fuzzy concepts that I instinctively distrust. (I also wrote an article once about masculinity, which is a term with no fixed definition.) I think I do find it satisfying to try to narrow all that vagueness down to some definite assertions, even though this also means that I risk being wrong in a big way, or at least that I risk landing very hard with some readers and not at all with others. (Some people read what I write about the Midwest and then email me to say basically “Nope” and then describe a completely different Midwest that I have never encountered. It’s just going to happen.) Also, of course, my wife asked me about it, which is the anecdote you’re referring to. She’s a Texan and she expected the Midwest to have distinctive, nameable cultural habits similar to those that Texans have, or that Southerners have. It turns out that we do but that we have trouble naming them, beyond the silly jokey stuff (saying “oop”; eating hotdish—interesting how many of these seem distinctively Minnesotan/North Dakotan). She thought it was weird how hard of a time we had talking about ourselves as Midwesterners, and once I saw that through her eyes, I thought it was weird too. If there’s a section of your own experience that you can’t describe without vagueness or cliche, something’s probably going on there.

As the title Midwest Futures suggests, you aren’t simply interested in the historical construction of the Midwest, but how ideas about the future shape people and policies. How do you see your role as a writer intersect with the work of imagining possible futures?

This question hits me kind of hard right now because I’m realizing that a possible future that I had really staked my heart on and even worked hard to actualize—Bernie Sanders possibly being President, a sweeping Green New Deal, Puerto Rico’s debt forgiven by a stroke of the pen, etc.—may not work out. (We’ll see how he does in the final debate.) But I think it’s very hard for people to imagine a future right now. We’re living in a time when it seems like we’re asymptotically approaching apocalypse—simultaneously like something absolutely horrible will happen soon and we’ll all be wandering around in rags afterward, and also like nothing will ever change, we will just recycle the same dull half-dead political figures and reconfigure a handful of threadbare ideas and reboot the same movies and every so often a celebrity will die and you’ll think, Didn’t they die a couple years ago? It’s an awful way to live. I don’t quite think my way out of it in the book but I wanted to try to begin to, for my own sake and for readers’ sakes. Doom and gloom have a place aesthetically and as a kind of mutually pleasing catharsis but past a certain point they’re not helpful. Till an asteroid wipes us all out we’ve got to keep trying to make the world livable for people after us.

You point to how varying visions of the future—including acquisitive, racist, expansionist, and utopian ones—have shaped the Midwest. In what ways do you see increasing awareness of climate change and pictures of apocalyptic scenarios shaping our plans for the future?

I think in the short term we have to worry about rich-people land grabs and especially about attempts to secure rights to the Great Lakes, since, you know, it’s kind of easy to see how the idea of selling off all that freshwater at a premium might excite some billionaire who foresees a hotter world. We have to fight to keep as much of that wealth as possible belonging to everyone. That’s going to require political vigilance and organizing. Native American activists are already fighting this battle, e.g. the Standing Rock protests and the protests against Enbridge Line 5. When you’re trying to fight the privatization of tons of freshwater, of a relatively fertile part of the country, etc., it’s not a bad idea to take at least some cues from people who have a history of believing that land can’t be “sold.”

Critical history seems so integral to this project. How did you approach the giant task of researching for this project? Do you have any advice for writers who are engaging with archives?

I will find the section of the library that roughly fits my topic and just grab everything that looks interesting. I use Google Books a lot because shockingly weird and obscure things are on there, including, in my book’s case, a source that some of the historians I consulted didn’t seem aware of. (It comes up in the book’s very first section.) It’s super tedious, and what keeps me going is just the idea that the actual facts of the case will always turn out to be more insane than whatever I’m imagining, and the book will be better and cooler and more interesting if I try to find those. When I first took creative nonfiction classes, there was this really poisonous idea that it’s OK to fabricate some stuff or conflate certain people together in order to make the story more aesthetically powerful. Aside from being dishonest and getting us bad books like A Million Little Pieces, or that memoir by that lady who said she’d been raised by wolves (!), this view also totally misunderstands the aesthetics of nonfiction. Part of what we enjoy about Janet Malcolm or Renata Adler is precisely those ill-fitting details that would seem extraneous if you were making all of this up, or the moments when they admit that their memory might be failing them. When I get exhausted with research, I remember my favorite moments in those writers, and think about what might still be out there waiting for me.

What do you hope might become possible if we can see the region and its imaginary a little more clearly?

I don’t know if this is just me being weird, but I feel like our culture is just pervasively insulting, pervasively trivializing, of all of us, most of the time. Billboards, commercials, movies, emails from HR, tweet threads that begin “Buckle up”: I feel like we talk to each other in ways that minimize everyone’s complexity. I want to live in a social world that doesn’t do that! A lot of my writing is me just searching for a register in which to speak that doesn’t feel to me like it does this. (And probably me not finding it.) I think that if we understood each other more slowly and more carefully, we might treat each other better. And if we then turned that enlarged imagination on to the incredibly beautiful and sometimes severe place where we live, we might treat it a little better. At least we might keep fracking fluid out of the groundwater more of the time. Who knows if I’m right, but that’s the hope.

“Does this sing?”: Artist Interview with Connor McManus

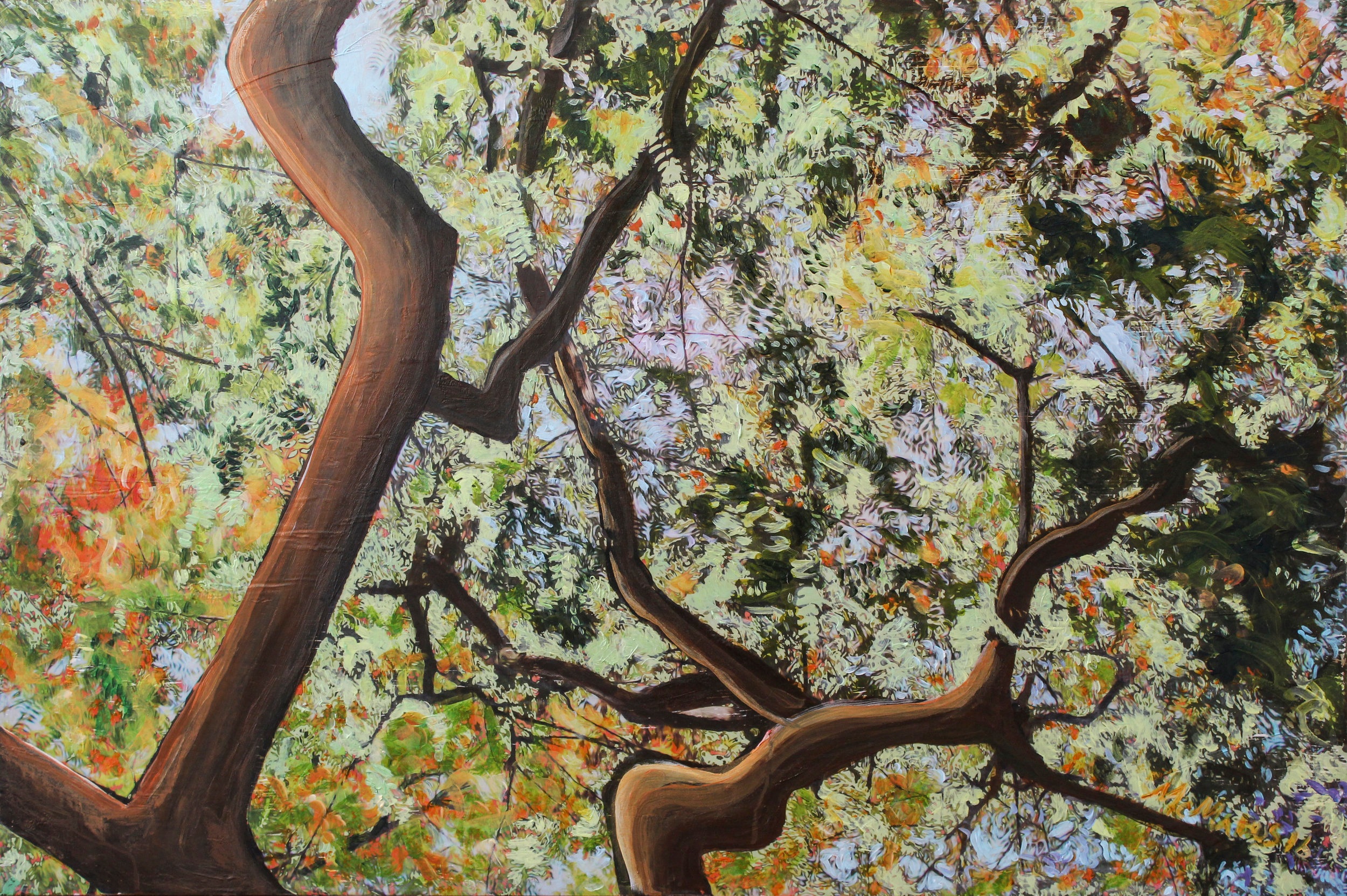

Poet Connor Simons interviews Minneapolis-based artist Connor McManus, whose painting “Wandered River” appears as the banner image on the new Great River Review website.

Connor Simons: Could you perhaps give us an ‘elevator pitch’ version of your artistic ethos? What, if any, underlying goal do you have when producing different works?

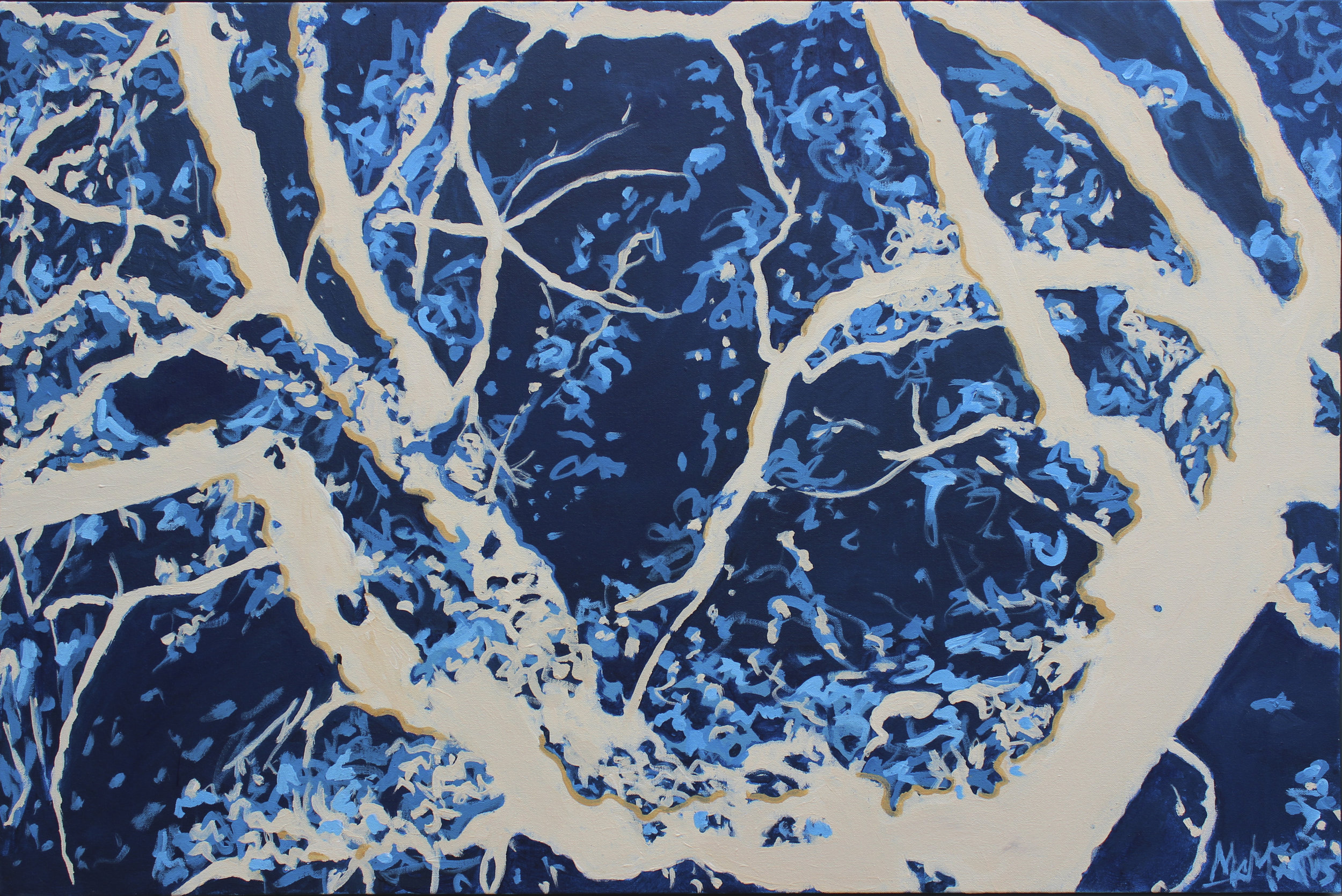

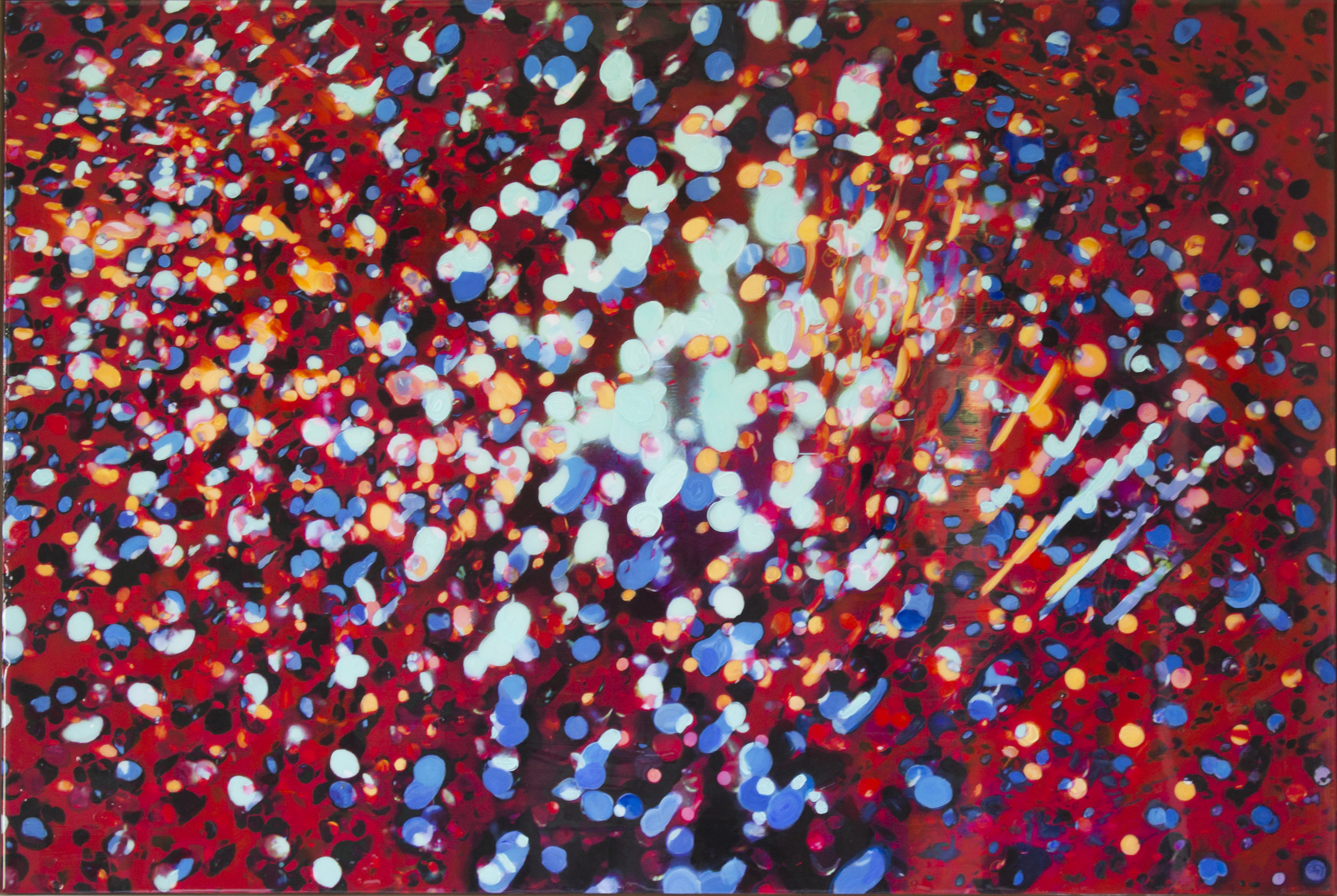

Connor McManus: Good question. Big question. My work is pretty varied, from naturalesque landscapes to kaleidoscopic mandalas, but there is a metaphor that I ground my aesthetic and self-criticism by, and that’s music. My test is, ‘does this sing, does this resonate’. That works for me on an intuitive level but also in closer analysis – how do the rhythms relate to the overall movement in the composition, how do the colors harmonize to suggest one mood or another. A piece is successful (and it’s not like they all are – sometimes it takes me a year later to see why something just didn’t work) it succeeds like songs succeeds – all the parts are well balanced to create the desired overall impression.

I read in an Alain de Botton book on beauty – architecture in particular – that we surround ourselves with the things we don’t want to forget, the things that remind us of what we are missing in our lives. Sometimes I think of my pieces in those terms too, knowing that they will end up on my or someone else’s wall. Take some of my pieces that are of trees but completely recolored – edging into the abstract – I think I do that to make something familiar seem new again, to remind people that the most common aspects of our surroundings are astonishingly beautiful. Those familiar things are easy to ignore. Those tree pieces are reminders of how strange and unlikely trees actually are – and by extension how unlikely any of this actually is – being itself. How they operate is a little like how seeing the world on mushrooms helps remind you of the big picture – the world is temporarily retuned, like you might retune a guitar, and you see all of it again with a fresh perspective. I aim for my work to hint towards that, because we all get rutted into our day-to-day work and painful, small dramas. When I make my work, I try to re-inhabit the wonder with which we once regarded the world, and hopefully that comes across in the finished pieces.

CS: As just about any millennial-aged ‘creative type’ knows, it is ridiculously hard to make a living as a ‘pure artist’. Could you tell us about the relationship between commercialism and artistry in your own artistic practice(s) and development as an artist?

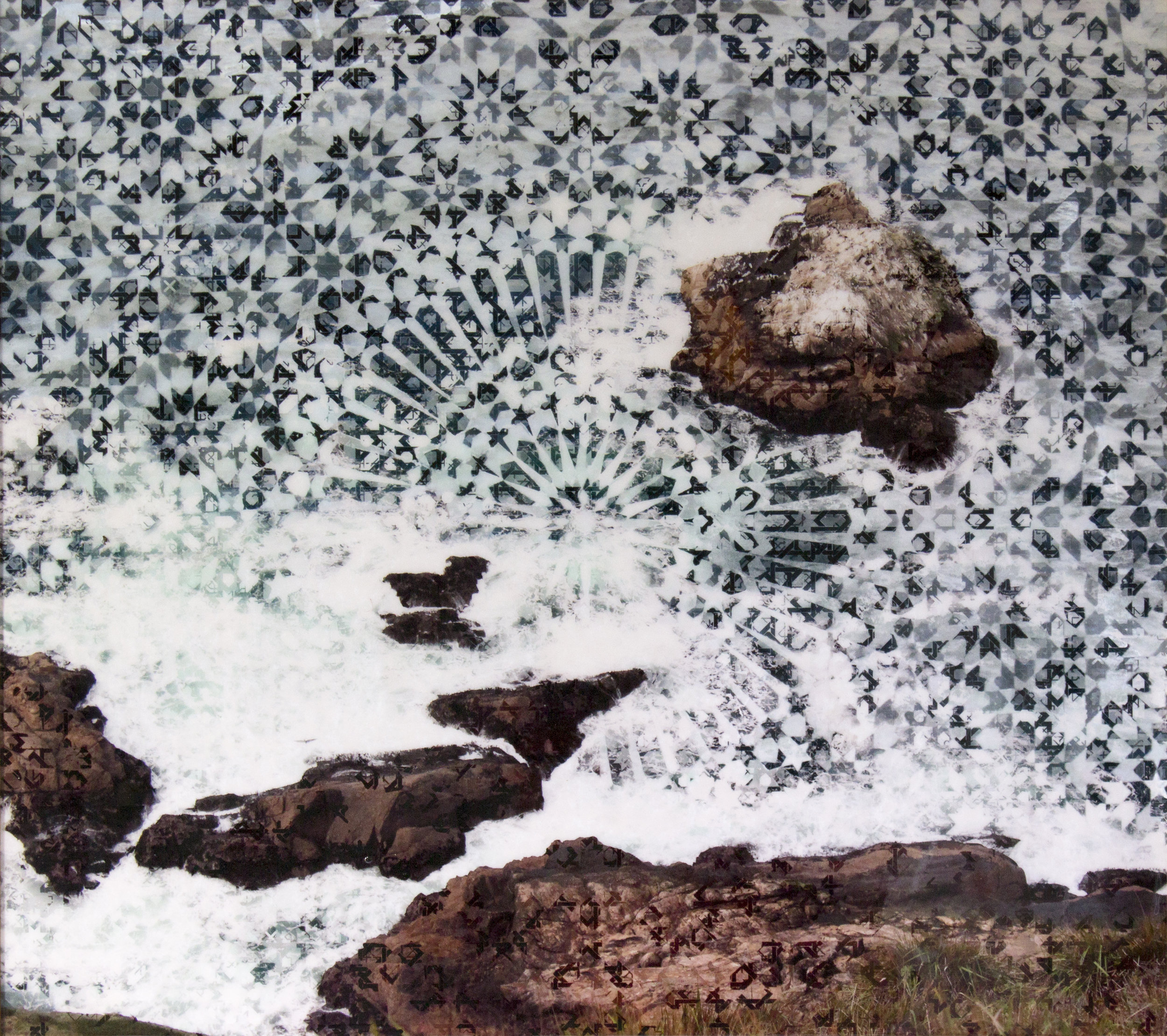

CM: Sure, and this ties into what I was just saying. I do view my work in the context of where it will be and who will be looking at it, and what positive impact it can have on that room, on those people. I make most of my living at an architecture firm, so I think like a designer too, where the art pieces are not the whole shebang, but just one component of a space with aims for the experience of the people in it. In New Orleans, where I lived for the past five years before moving to Minneapolis, I built a great relationship with a group, Where Y’art, which connects me with commercial buyers like the new hospitals which have been expanding since Katrina. They have commissioned a lot of my more natural work, and have bought prints and remarked giclees (a pretentious way to say prints on canvas with additional paint added). Sometimes they request that I make a new version of an old piece but in different colors (they can’t have the color red, or images of birds (for some reason birds are particularly morbid) on their walls). I think this type of commercial relationship is becoming more common for a lot of artists, but maybe if I were in New York or in some big galleries this would be a no-no, because the value of art is tied to exclusivity and some sacrosanct notion of artist as untainted by plebian desire for pretty decoration. But you look at that attitude from a moral perspective and it’s reprehensible. Insofar as I want people to gain something positive from my work, of course I would extend that to people who are in the unfortunate circumstances of sitting in a hospital waiting room. Otherwise, you sell a piece once, to the richest person you can find, and then they and their rich friends are the only people who ever appreciate the work. Also, because I design most of my work in photoshop, collaging and sampling from photographs, I have 20 alternate versions of every piece I make – they’re like B-sides or remixes. So I enjoy going back to old work and reworking for a particular need. If the piece can sing in its own right and be tuned to the key of a room, to function on the architectural scale, making a space beautiful in a place not normally associated with beauty, I think that’s a good thing.

CS: Obviously, Great River Review is primarily geared towards writers and poets. What intersections/relationships do you see between the written arts (poetry, nonfiction, and fiction) and visual arts (whether as a whole or in your own work)?

CM: Well there are a couple of intersections that I see there. First is, on the visceral level, in poetry and fiction in particular perhaps, writers can articulate aesthetic details in more depth and from more angles than can be gleaned from an image. They have recourse to layering in the other senses, concurrent thoughts and emotions, and associated memories, which taken all together form the aesthetic punch. A painting can show you the beauty of a flower, but writers can put you right in the mental space from which that beauty springs forth, so you can share the experience of someone really being moved by simple, persistent beauty. That’s recourse to drama. Maybe your mom passed away a year ago, and she was a gardener, and you’re here trying to keep the damn weeds from taking over your patio, and the dirt is under your fingernails, the wriggle of an earthworm scares you for a second, the sweat is on your brow, clothes sticky, scent of cut grass from your neighbors’ lawns, and while you sit here crouched and uncomfortable and sore and sad, you notice a flower that your mom told you about once sprouting up three feet away, and you move closer and admire it. There’s so much more context to layer in there than visual artists have at their grasp, although I think that’s why so many great paintings have an implied narrative built in. Take Japanese prints of mostly landscape, but somewhere in the middle-distance there’s a bridge and tiny figures walking across hastily through the rain. The beauty of the scene hits you with a whollop because there are those people in the narrative space, who have a past and a future, captured in this fleeting moment, their immediate motivation so clear and relatable. So, drama. We can hint at it, but you can work with it so much more to charge up those aesthetic observations with meaningful overtones.

I also do think drama has those same musical elements I was discussing earlier. It’s the layering of imagery, themes, plot, characters and their foils, and the structural rhythm at whatever scale – poem, chapter, or book - that function to me much like the different elements of a song or album. As the drama unfolds, those elements grow and interplay with each other, creating harmony or dissonance – rewarding the reader with a good balance between expectation and surprise. I think that musical element still applies, and is a good bridge metaphor between the two, because music shares literature’s narrative element, although music is typically more abstract. In visual art, that narrative or temporal dimension is compressed and flattened into two-dimensions on the canvas, and appears as abstracted visual movement or the suggestion of figurative drama like the people on the bridge.

CS: Do you have a mode or modes or visual art that you’re particularly drawn to? Why?

CM: Yes. In college, I started using Photoshop as a design tool to compose my work. Prior to that I would just paint abstractly and follow my whims until something looked finished. Although Photoshop gives me more control, it also gives me way more freedom, because I can quickly test things out (and hit undo!), manipulate images in many different ways, combine and layer things, sample, cut, crop, recolor, etc. Every medium has its motivation, though. Photoshop tends towards imagery that looks very digital and cold. So when I work with it I’m often pushing against that tendency, trying to make compositions that are painterly, and I usually resolve that through actually painting the composition (or painting over it) and using gestural intuition in the last 10% of the process. But by that time, I know what colors I want, I know the overall form and compositional intent. It’s like composing music on the computer and then re-recording with instruments after it’s all arranged. It feels right to me in terms of the tools available to produce what’s possible in this moment.

CS: What inspires you in your artistic practice(s)?

CM: Nature and music, mostly. I love the fractals in trees and other natural forms, how they reappear all over the world and are echoed in religious designs and architecture, how they are rooted in math, and likewise how musical harmonics break down into a pattern-language of vibration. I’ve spent some time investigating how to translate the basic thing that happens when music hits your ear – why do chords sound good, for instance, and the answer is basically that your earls like simple geometry of waves that sync up in a predictable way. The ratios of the wavelengths of the individual notes that compose chords sound good together because their wavelengths (or frequencies) lock together into repeated patterns, with simple ratios like 4:5:6. I’ve been playing with those properties in some of my recent work, trying to visualize this phenomena that humanity has appreciated with our ears forever. What fascinates me about this is that the same kinds of simple harmonics are appreciated in architecture and classical proportions. I think there is an element of beauty that is deep on the biological level – that these basic relationships and proportions resonate in the most basic sense with how nature patterns itself, and in turn – insofar as we register nature as beautiful - how we perceive our own creative abstractions to be beautiful. The closer they are to natural principles – the principles our ears naturally decode in music – the more universally beautiful the production is.

CS: Which visual artists working today, regardless of the medium, do you find particularly exciting?

CM: I really love Julie Mehretu. Her work is…well, I would say it embodies a lot of what I’ve already described. She makes large pieces that from afar are ethereal – like you’re looking at a cloud or an indistinct cacophony of imagination composed of many small, usually black or grey marks. As you get closer, the meta-image breaks down into smaller vignettes, you can see pieces of architecture or abstract mini-narratives dance across sections of the piece. And all the way down, down to each line or blot, she uses this great variety of mark-making, from anal architectural precision to painterly gesture. These marks are arranged in the Z plane on many layers of clear medium, so her work has a shallow depth that pushes some things back and brings others forward. It creates a sense of memory and association, newer ideas obfuscating or augmenting the previous. Looking at her work is like seeing a visualization of a memory palace – too vast and complex and personally encoded to understand, but at the same time familiar, and well, natural.

CS: Thank you for taking the time to have this interview with me, and thank you for contributing to Great River Review

Connor McManus’ work can be found at:

Website: connormcmanus.com

Online store: https://whereyart.net/artist/connor-mcmanus/315

Facebook: Connor Mcmanus Art

Instagram: @mkmanus

A Hunger for Words: An Interview with Peter Campion

In the wake of Great River Review's first issue published through the University of Minnesota's English Department, editor Peter Campion talks about the past, present, and future of the journal.

This is the first issue of Great River Review published through the University of Minnesota’s English Department. How did the department come to take over Great River Review? How did you come to be its editor?

We were fortunate to be offered the stewardship of Great River Review by its previous editor, Robert Hedin, a marvelous poet who, until his recent retirement, directed the Anderson Center in Red Wing. He wanted the journal to continue, and we were grateful for the gift.

I’d been, for five years, the editor of another journal, Literary Imagination, and was eager to share my knowledge with graduate students here at the U. Periodicals are a vital element of literary culture, so it makes sense for our students to have experience working on them. For my part, it’s also a lot of fun to be in a place where everybody’s getting their hands dirty producing something.

Now that GRR is in a new location, what changes do you anticipate making to its aesthetic, if any? What kind of work do you envision publishing in the future?

Something I admire about the way Robert edited the journal—he didn’t seem to have “an aesthetic” as such. He simply published work that he considered first rate. I hope to do the same. I just want to support the best poetry, fiction, and non-fiction. As a reader, I’m eager to be astonished by superb new writing, regardless of any affiliation.

Something I’m dedicated to publishing more of is good criticism. Book reviewing is a great way for emerging writers—any writer, in fact—to get involved in the larger conversation. Since so many newspaper book sections have gone the way of the Tasmanian tiger, it falls to the little magazines to keep that conversation going. And I’ve found that readers appreciate this.

Great River Review is published in conjunction with a graduate-level course offered by the English Department. What do you want students to take away from the experience of talking about literary magazines and creating one?

Not only does this course offer a chance to gain experience in editing and producing a journal, it also gets students to explore the rich history and present of periodical publication in America. When we research the great modernist poets, for example—Pound, Eliot, Williams, Moore, et al—we need to learn about magazines such as BLAST, Contact, The Dial. And similarly important moments in literary history, such as the Beat movement or the Black Arts Movement had magazines such as Evergreen Review and Freedomways. In such venues, various art forms, as well as personalities, ideas, and styles rub up against one another. Every student in the course researches one such moment in literary history by examining a publication of their choice. And we dedicate the same level of attention to journals being published right now.

What’s more, we meet with professionals in the literary publishing world of the Twin Cities, in order to glean some of their wisdom. So, I want students to take away some important skills, but also to develop a well-rounded sense of how art, for all of its formal autonomy, also grows from the energy within various, overlapping communities.

Speaking of community, the Twin Cities has a dynamic literary scene. What do you hope GRRadds to it?

I want the magazine to capture some of the energy of that scene, in all its variety, and present that to the world at large. At the same time, since we’re not a regional magazine as such—we publish authors from all over—I want to bring great writing from all over the world into the fold of the Twin Cities community.

What do you hope will distinguish Great River Review within the world of literary magazines?

There are so many literary magazines I admire—AGNI, Threepenny Review, Raritan, North Ohio Review, just to name a few—so my ambition’s not competitive. I simply want the magazine to be really good. But there’s one characteristic all my favorite magazines share: I mean their utter disregard for borders between scholarship and creative writing. My favorite magazines are neither cloistered by professionalism nor hampered by anti-intellectualism. In fact, their editors seem to share a wholesome distaste for isms in general. After all, no one goes to a bookstore or a library thinking, “gee, I really want to read some good creative writing,” or “I’m looking for some fantastic literary scholarship.”

Those aren’t idiomatic sentences, and for good reason. People want to read stories, poems, and essays, or delve into a certain subject, or track down everything by a favorite author. A reader’s desire is appetitive. Reading is feasting. That’s something I’m so heartened by as I see the graduate students at UMN, students in both the creative writing and the literature programs, working together: they’re hungry for such experience. And that truly excites me.